Fermenting Beer with White Labs WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend

Published: February 9, 2026 at 6:54:29 PM UTC

White Labs WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend offers a fresh spin on farmhouse ales. It combines the lively spirit of Saccharomyces with the subtle funk of Brettanomyces.

When fermenting with WLP670, aim for temperatures between 68°–72°F. Attenuation will likely reach the mid-to-high 70s. The early sections will delve into pitching rates, oxygenation, and simple mash options. These are based on the Briess American Farmhouse Ale extract-with-grain recipe and White Labs product specs.

Whether aiming for a 15 IBU session farmhouse or a long, Brett-driven conditioning, this guide will assist. It covers setting up primary fermentation, choosing a vessel, and monitoring gravity. Practical tips include using Servomyces for nutrient support and examples of OG/FG pairs for ABV predictions.

Key Takeaways

- White Labs WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend pairs Saccharomyces and Brett for balanced farmhouse character.

- Target a 68°–72°F fermentation window for clean ester development with subtle Brett complexity.

- Expect 75%–82% attenuation and medium flocculation; plan recipes and mash profiles accordingly.

- Use oxygenation and nutrients like Servomyces to support a healthy, predictable fermentation.

- Decide early whether you want a short primary (14 days) or extended conditioning for Brett evolution.

What is WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend

WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend is a commercial mix from White Labs. It aims to merge farmhouse and wild flavors into one package. Brewers opt for it to achieve Saison-like spice and Brettanomyces complexity without the hassle of managing multiple cultures.

Composition and origin

The WLP670 blend combines a traditional farmhouse/Saison yeast with Brettanomyces strains. This combination creates complex aromas and allows for long-term development. White Labs markets it as WLP670 American Farmhouse Blend. The brewing community often credits U.S. craft brewers like Tomme Arthur and The Lost Abbey for its influence. They are known for their work with mixed fermentations.

Intended brewing styles and inspiration

This blend is perfect for Berliner Weisse, Flanders-style ales, lambic-inspired beers, wild specialties, farmhouse ales, and Saisons. White Labs recommends these styles for its intended use. Homebrewers and professional brewers use it to create semi-traditional Belgian flavors with American malt and hop choices. It also helps achieve a controlled, moderate sourness alongside fruity and peppery esters.

Comparison to single-strain Saison and Brett blends

Many brewers choose WLP670 for its unique blend of Saison and Brett characteristics. It offers classic Saison esters and Brett-derived flavors like leather, cherry, and green apple without the need for separate cultures.

- The blend simplifies workflow and can cut costs versus buying a Saison strain and a Brett strain independently.

- Brewers report a balance often near a 45% Saison to 55% Brett impression in finished beer, yielding spice and phenolics with wild, fruity Brett tones.

- Using a single mixed vial reduces contamination risk and makes timing Brett activity easier to manage during conditioning.

Key Fermentation Characteristics of WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend

WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend is known for its lively, dry profile. This section explores its behavior in gravity drop, settling, and alcohol limits. This knowledge helps in planning recipes, pitching, and aging with confidence.

Attenuation and expected gravity drop

White Labs reports WLP670 attenuation at 75%–82%. In practice, a Briess extract with OG 1.046 finished at FG 1.012, showing about 72% apparent attenuation. An all-grain brew starting at OG 1.061 reached FG 1.004, aligning with the high attenuation expected.

When planning your original gravity, keep in mind the yeast's tendency towards a dry finish. This is typical of farmhouse and Saison beers. If you prefer more body or residual sweetness, adjust mash temperatures or fermentables. This will help compensate for the robust gravity drop and target the expected FG with WLP670 for accurate ABV calculation.

Flocculation behavior and clarity expectations

White Labs rates WLP670 flocculation as medium. Early in fermentation, active yeast clears reasonably well. However, the Brett component can introduce a slow haze or gradual clarity shifts over time.

Expect moderate settling in primary fermentation. Extended aging or secondary conditioning may alter clarity as Brett continues its slow activity. Filtration, fining, or additional time may be necessary for a bright, clear beer. Monitor WLP670 flocculation during conditioning to achieve desired clarity.

Alcohol tolerance and how it limits recipe strength

WLP670 has a medium alcohol tolerance, roughly 5%–10% ABV. Beers above 10% ABV may stress the blend, leading to stalled fermentation or a sweeter finish if the yeast reaches its limit.

For high-gravity saisons, consider staggered pitching, careful nutrient control, or co-pitching with a higher-tolerance Saccharomyces strain. Monitor specific gravity closely. Keep WLP670 alcohol tolerance in mind when setting OG to avoid unexpected residual sugars.

Optimal Fermentation Temperature Range and Management

WLP670 yeast is highly sensitive to temperature. To achieve a balance between esters and Brett character, fermentation should be kept within a specific range. This range helps avoid harsh phenolics. Brewers often follow White Labs' guidelines and recipe notes, recommending a moderate temperature of 68-72°F for consistent results.

- Suggested window — Target the middle of the range for optimal results. A consistent temperature allows Saccharomyces to produce fruity esters without excessive spice. Meanwhile, Brett can develop gently.

- Why it matters — Maintaining a temperature between 68-72°F reduces yeast stress. It promotes clean attenuation and minimizes the risk of phenolic off-flavors associated with extreme temperatures.

Suggested temperature window (68°–72°F) and why it matters

White Labs recommends an optimal temperature range of 68°–72°F (20°–22°C) for WLP670 yeast. This range supports balanced ester production and efficient attenuation. Following the Briess extract guideline, which suggests 14 days at 72°F, ensures a predictable and solid fermentation outcome.

Temperature ramping strategies for farmhouse character

Temperature ramps can influence the farmhouse flavor profile. Start fermentation slightly cooler to encourage healthy yeast growth. Then, allow the yeast to warm naturally over a few days. A brief warm period after active fermentation can enhance ester and Brett expression, adding complexity to Saison-style beers.

One common approach involves starting near 64°F, allowing a self-rise to about 70°F over 48–72 hours. The fermentation then holds at this temperature for the main attenuation phase. Finally, a brief warm period in the low–mid 80s°F range is used to accentuate esters and Brett activity. This method accelerates attenuation and brings out funk without disrupting balance.

Practical tips for homebrewers to maintain stable temps

- Employ a fermentation chamber, swamp cooler, or a chest freezer with a temperature controller for reliable homebrew temp control.

- For minor increases during ramping, use heat wraps or a controlled heater and monitor with a probe thermometer.

- Avoid sudden, large temperature swings. Ramp slowly over 24–72 hours to reduce yeast stress and lower the chance of off-flavors.

- Log temperatures and gravity readings. Small adjustments early are easier than corrections later.

Pitching Rates, Oxygenation, and Yeast Health

Ensuring the right pitch and oxygen level is crucial for a clean, active fermentation with WLP670. Below, we provide practical guidelines for 5-gallon batches. We also discuss proven oxygenation methods and the use of nutrient supplements to protect WLP670 yeast health.

- White Labs offers a pitch rate calculator. A single fresh vial often suffices for a typical 5-gallon batch. Many homebrewers achieve success by pitching one fresh vial without a starter for average OG beers.

- For high gravity recipes or beers with lots of adjuncts, a starter is recommended. It raises cell count and lowers the risk of a sluggish start. Stressed fermentations benefit from a stronger inoculation.

- When planning, treat WLP670 pitching rate as a variable tied to gravity and recipe complexity rather than a fixed rule.

How to oxygenate wort before pitching

- For extract batches, vigorous shaking or splash transfer into the fermenter adds enough dissolved oxygen for small-volume beers. Aeration by hand works in many cases.

- All-grain brews often need more dissolved oxygen. Use pure oxygen with a diffusion stone or a sanitized pump and tubing for vigorous aeration.

- Follow recipe notes that instruct when and how to aerate. Proper practice during wort transfer supports yeast reproduction and early activity.

Use of nutrients like Servomyces and impact on fermentation

- Adding Servomyces yeast nutrient in the boil, as some recipes recommend, provides trace minerals and nutrients that boost yeast vitality.

- Nutrients reduce the chance of slow starts, help consistent attenuation, and can lower off-flavors such as sulfur compounds, especially when the grist includes adjuncts like corn or simple sugars.

- For blends containing Brett, nutrient support and correct oxygenation aid early Saccharomyces growth. This shapes the long-term activity and flavor contributions of the mixed culture.

Pay attention to cell counts, oxygen technique, and nutrient additions. Doing so protects WLP670 yeast health and improves the odds of a reliable, flavorful farmhouse fermentation.

Fermentation Timeline and Vessel Choices

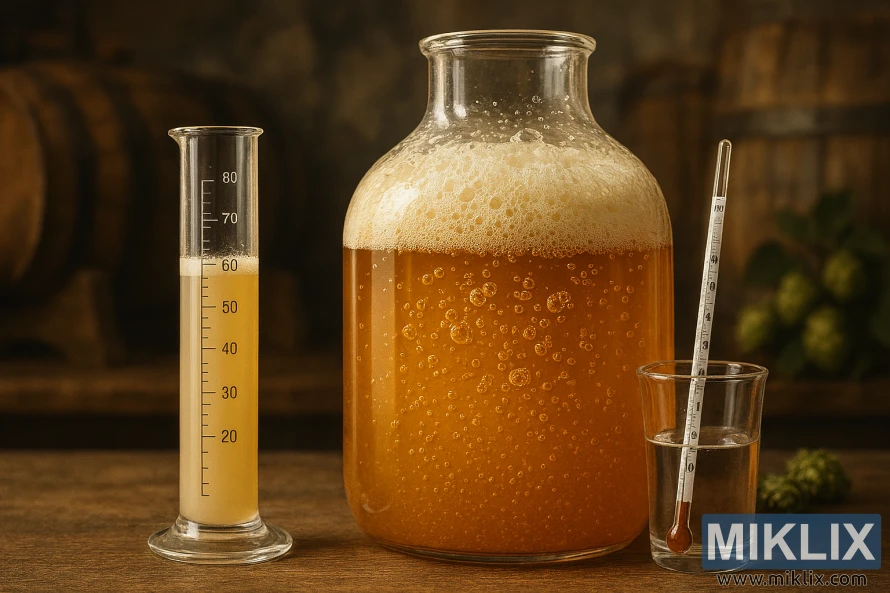

Understanding WLP670's behavior over time is crucial for planning brewing and aging. The primary fermentation phase can be rapid at first, then slow as Brettanomyces takes over. The choice of vessel impacts sanitation, ease of racking, and the aging process of Brett.

Primary fermentation expectations involve timing and visible signs. With a Briess extract recipe, a 14-day fermentation at 72°F is a practical guideline. Brewers often see vigorous krausen and airlock activity in the first days, followed by krausen collapse and clearer beer.

Gravity continues to fall after the main ferment. Yeast quickly consumes simple sugars, while Brettanomyces slowly metabolizes complex sugars. Tracking gravity over weeks reveals steady declines rather than a sudden end.

Signs of slowing fermentation include sediment settling, a thinning krausen, and reduced CO2 release. Use a hydrometer or digital refractometer to confirm these trends before transferring or packaging.

Brett aging is crucial after primary fermentation. Brettanomyces adds flavors like leather, cherry, and green apple over weeks and months. Extended aging allows these flavors to develop and integrate into the beer's profile.

Extended aging can be done as a long primary with Brett or moved to a secondary vessel for conditioning. Keeping beer on the yeast and Brett in bulk reduces oxygen exposure and packaging risk while allowing complexity to grow.

- Short conditioning: a few weeks to mellow rough edges.

- Medium conditioning: 1–3 months for balanced Brett contribution.

- Long conditioning: 3 months or more for pronounced Brett aging and moderate sourness.

Fermenter choices for Brett impact both results and cleanup. Stainless conicals are durable, easy to rack, and thoroughly sanitize. They are ideal for mixed-fermentation work and minimize cross-contamination risk.

Glass carboys are inert and allow for observing clarity and sediment. They can break and are heavier, but many hobbyists prefer them for visual checks during Brett aging.

Food-grade plastic fermenters are light and affordable. Scratches may harbor Brett, making dedicated use or careful replacement necessary for Brett-containing beers.

For mixed-fermentation projects, choose equipment with rigorous sanitation options. Stainless is easiest to sanitize and suitable for repeated use. If using glass or plastic, consider dedicating some gear to Brett work to protect neutral ales from unintended infection.

Recipe Examples and Mash Profiles for Farmhouse Ales

This section provides a practical extract-with-grain recipe and detailed mash guidance for brewers aiming for farmhouse character. It showcases how mash temperatures and adjunct choices influence attenuation, body, and rustic notes in WLP670 recipes.

Sample extract-with-grain recipe for 5 gallons (based on Briess recipe)

- 3.3 lb CBW Golden Light LME

- 0.5 lb CBW Sparkling Amber DME

- 2.0 lb Red Wheat Malt (mini-mash)

- 2.0 lb Flaked Yellow Corn (steep with grains)

- 0.5 oz Crystal hops (60 min), 0.75 oz Crystal hops (15 min)

- 1 vial WLP670

- 1 capsule Servomyces (boil 10 min)

- Mini-mash with 4 gallons water, steep 30 minutes at 152–158°F, add extracts, boil, cool to 72°F, oxygenate, pitch

- Target OG 1.046, FG 1.012, ABV ≈ 4.7%, IBU ≈ 15, Color ~6 SRM

All-grain mash temp recommendations and effects

For all-grain brewing, aim for mash temperatures between 152–158°F. This range balances fermentability and body. A lower mash temperature, around 152°F, promotes enzyme activity, leading to a drier, saison-like finish. Higher temperatures, near 158°F, result in more dextrins, enhancing mouthfeel and residual sweetness.

Brewers seeking extreme attenuation might mash cooler or use single-step decoction. For instance, a 149°F mash for 90 minutes can produce a very fermentable wort. Adjust conversion and rest times to fine-tune the final body in all-grain mash temperatures for farmhouse ales.

Adjuncts and specialty grains to accentuate farmhouse character

Farmhouse adjuncts add texture, rustic grain notes, and fermentability. Wheat malt and flaked oats improve head retention and silkiness. Flaked corn lightens the body and introduces a dry, grainy character, as seen in the Briess American Farmhouse Ale recipe.

Small percentages of specialty malts, like Belgian Caravienne or a touch of crystal, add color and malt complexity. Rye contributes spicy, savory flavors. Golden naked oats offer smoothness without huskiness. Corn sugar, when used, pushes attenuation and dryness.

When crafting recipes, distribute adjuncts to support yeast performance and the desired final gravity. WLP670 recipes benefit from modest adjuncts that enhance fermentability, allowing farmhouse esters and Brett character to shine.

Hops, IBUs, and Balancing Flavor with WLP670

To balance hops with WLP670, use a light hand. This allows the yeast-driven farmhouse character to shine. Aim for a modest bitterness. Use hop choices and timing to enhance esters and Brett complexity without overpowering them. Here are some practical guidelines and pairing ideas for a bright, restrained finish.

Farmhouse beers typically have low bitterness. A farmhouse IBU 15, as seen in the Briess example, provides a crisp backbone. This lets yeast and Brett notes shine. Brewers often target 10 to 25 IBUs for saisons and farmhouse ales to keep them refreshing and balanced.

When selecting hops, choose those that complement yeast esters, not compete with them. American hops with citrus and floral notes pair well with WLP670. Amarillo, for example, adds bright orange-citrus top notes that complement Brett's funk. For a more peppery green character, traditional European noble or spicy hops are suitable.

- For bright, fruity character: Amarillo, Citra, and Cascade.

- For spicy or noble balance: Saaz, Styrian Golding, and Hallertau.

- For subtle complexity: small blends of American and noble hops to avoid dominance.

For farmhouse beers, hop timing is key. Use a modest 60-minute charge for base bitterness. Reserve aroma hops for whirlpool and late kettle additions. Dry hopping can enhance aroma without increasing bitterness if done lightly and briefly.

- 60-minute: small bittering addition to hit target IBUs, e.g., 10–15 IBU total.

- 15–5 minutes: measured additions for flavor, not punch.

- Whirlpool/dry hop: aroma focus; short contact to protect delicate yeast esters.

When planning hop schedules, remember to enhance, not hide, the yeast blend. Keep additions modest and space them for clarity of flavor. Test small batches if you explore bold WLP670 hop pairings.

Managing Brettanomyces Contribution and Sourness

The presence of Brett in a farmhouse blend offers a dynamic, evolving beer profile. Brewers note a blend of funk, oxidative notes, and bright fruit that evolves over time. It's crucial to monitor this development to maintain the desired beer character.

How Brett in the blend affects flavor development

Brett imparts unique Brett leather cherry green apple notes, cherished by many brewers. These flavors span from leathery, barnyard tones to tart cherry and crisp green apple. In WLP670, Brett's fraction is distinct, often making up half the beer's mature character.

Controlling moderate sourness: time, pH, and blending

Sourness from Brett develops gradually as acids accumulate during aging. Time is the primary factor; shorter cellaring periods limit acid buildup. Monitoring pH during aging helps detect trends before acidity dominates.

When a batch becomes too tart, blending with a fresher, non-acidic batch can restore balance. This approach maintains complexity without introducing a sharp, kettle-sour profile. The WLP670 blend, lacking acid-producing bacteria, results in moderate sourness rather than intense tartness.

Sanitation and separation to avoid cross-contamination

Brett can survive routine cleaning, necessitating strict Brett sanitation in mixed-ferment beers. Use dedicated fermenters and hoses or separate bottling and kegging paths for Brett-forward brews to safeguard neutral styles.

- Sanitize fermenters, siphons, and bottles with a proven agent after each Brett batch.

- Rinse and inspect gaskets, valves, and hard-to-clean fittings where Brett hides.

- Label and store Brett equipment separately to reduce accidental transfer.

Effective Brett sanitation is essential for any brewery or home setup. It minimizes cross-contamination risk, allowing for the management of Brettanomyces flavors and sourness through timing, pH monitoring, and blending.

Fermentation Profiles and Case Study Brewing Schedules

This section explores practical schedules and real-brewer outcomes for farmhouse ales using mixed cultures. It details a stepped approach to shape ester profiles and Brett development. The examples highlight timing, temperatures, and the trade-offs between short and long primary fermentation.

Example stepped temperature plan:

- Pitch near 64°F and hold for 24 hours to encourage a clean start.

- Allow yeast to self-rise to about 70°F over 48 hours, then hold one day to establish steady activity.

- Let the fermentation drift naturally for two more days before applying heat.

- On day 6–7, raise temps to the low–mid 80s°F for four to five days with heat wraps for warm conditioning.

- Return to room temperature until activity slows, then cold crash and package.

The stepped temp Saison schedule leads to a cleaner early ester phase, followed by intensified phenolic and Brett-driven notes during warm conditioning. This phased rise balances saison esters with Brett funk. It's ideal when using the WLP670 fermentation schedule as a template for mixed cultures.

Short primary versus extended aging has distinct outcomes. A shorter primary around 14 days at 72°F can finish with a bright farmhouse profile and only moderate Brett character. Many commercial recipes from suppliers such as Briess follow this timing for predictable results.

Extended primary or bulk aging lets Brett continue to attenuate and transform flavors over weeks to months. Expect FG to drop further with time. Aromas move toward leather, barnyard, and subtle fruit notes. Mild sourness can creep up, driven by long-term Brett activity and microbiome shifts.

Real brewer notes from a long primary Brett case study are instructive. One homebrewer reported more than 90 days in primary before bottling. Another all-grain example reached OG 1.061 and dropped to FG 1.004 after prolonged conditioning.

Brewers described Brett contribution as stronger than the Saison yeast in those long runs, roughly a 55% Brett influence by character. Tasting notes listed leather, cherry, and green apple among the dominant descriptors, with an overall balance that favored complexity over immediate drinkability.

Use the WLP670 fermentation schedule and a stepped temp Saison schedule when you want to control early ester character and then promote Brett evolution. If planning a long primary Brett case study, prepare for ongoing gravity changes and a gradual shift toward funk and depth rather than a quick, clean finish.

Measuring and Interpreting Gravity, ABV, and Attenuation

Accurate gravity readings are crucial for tracking fermentation progress and determining the best time to package. With a mixed culture like WLP670, the final gravity can vary widely. This variation depends on the mash's fermentability and the Brett's activity level. Use a calibrated hydrometer or digital refractometer for precise measurements. Record readings daily at the same temperature to ensure accurate comparisons.

For a lighter extract brew, expect an OG of 1.046 finishing at FG 1.012. This results in a beer with an ABV under 5%. On the other hand, a more attenuative all-grain mash could start at OG 1.061 and drop to FG 1.004. This is due to highly fermentable wort and Brett's contribution. Dry, farmhouse-style beers typically have final gravities in the low 1.000s.

To calculate WLP670 ABV, subtract FG from OG, multiply by 131.25, and round to a sensible precision. For example, an OG of 1.046 and FG of 1.012 yields an ABV of about 4.7%. However, if the OG is 1.061 and FG is 1.004, the ABV increases significantly due to high attenuation. Always log OG and FG to calculate apparent attenuation and compare it to the strain's typical range of 75%–82%.

- Apparent attenuation = (OG − FG) / (OG − 1.000) × 100.

- Track gravity over 3–5 consecutive days; stable numbers mean active fermentation has paused.

- Remember Brett can produce a slow, steady gravity decline over weeks to months.

Deciding when to package Brett beer requires both numbers and tasting. Stable gravity across several readings is necessary before bottling or kegging. Tasting for off-flavors and balance is equally important. If flavor still develops or you expect Brett to further dry the beer, give it extra bulk aging to reduce the risk of overcarbonation in bottles.

When to package Brett beer depends on gravity stability and your carbonation plan. For kegging with force carbonation, you can be more aggressive once gravity is steady. For bottle conditioning, wait until gravity has been flat for multiple checks and the palate matches your target profile. If residual fermentable sugars remain, store bottles cold after carbonation to slow Brett activity and limit pressurization risk.

Packaging Considerations and Conditioning with Brett Present

Brettanomyces changes how you package and condition farmhouse ales. Choices made at bottling or kegging affect carbonation, flavor development, and safety. Below are practical options and checks to help manage active Brett and the long-term evolution of your beer.

- Bottle conditioning vs. kegging with active Brett: Bottle conditioning Brett can drive continued attenuation in bottles. This yields evolving flavors and natural carbonation over time. Expect shifts in aroma and mouthfeel as Brett metabolizes residual sugars. This method raises the overcarbonation Brett risk if gravity was not stable before priming.

- Kegging allows force-carbonation and controlled cold-crashing. Use kegs when you want predictable CO2 levels and lower chance of bottle overpressurization. Kegging also simplifies filtering or blending out of overly active yeast prior to service.

- Carbonation strategies and monitoring for overcarbonation risk: When bottle conditioning Brett, err on the side of less priming sugar. Confirm gravity stability over several weeks before sealing bottles. Consider using smaller priming amounts and longer conditioning time to reach target carbonation slowly.

- Monitor for bulging caps or rattling bottles as warning signs. Condition at cooler cellar temperatures to slow Brett activity once desired carbonation is near. If you see early pressure signs, chill suspect bottles and move them to a beer fridge or keg.

- Cellaring potential and flavor evolution over months: Brett beers reward patience. Over months, Brett character deepens, with funk, fruit, and complexity emerging. Many brewers note favorable change after 90 days of conditioning.

- Store at steady cool cellar temps to allow gradual development and to limit sudden flavor jumps. Proper storage supports long-term plans for cellaring farmhouse beer and helps retain balance between acidity, funk, and malt presence.

For packaging Brett beers, document OG and FG, choose conservative priming, and plan storage. If you favor consistency, keg and force-carbonate. If you value evolving complexity, bottle conditioning Brett works but demands vigilance against overcarbonation Brett risk and patient cellaring farmhouse beer to reach its best expression.

Troubleshooting Common Fermentation Issues

WLP670 troubleshooting starts with careful checks. First, verify temperature, gravity, and sanitation. Often, small tweaks can solve common problems without major changes.

Stalled fermentations often have simple causes. Ensure the fermentation temperature is within the recommended range. Check oxygenation and nutrient levels; adding yeast nutrient or energizer can restart fermentation. If yeast viability is in doubt, consider repitching with a fresh Saccharomyces strain or blending with a more tolerant yeast for high-gravity batches.

For stalled fermentation with Brett, test gravity over several days to confirm the stall. Avoid immediate racking or bottling. Gentle warming and mild agitation can help. For high original gravities beyond WLP670's tolerance, blend with a stronger strain to finish attenuation.

- Check temperature and gently raise 2–4°F.

- Measure gravity at 48-hour intervals to confirm progress.

- Add nutrient or oxygen early in fermentation, not after weeks of inactivity.

Off-flavors need diagnosis by smell and context. Brett off-flavors like leather and barnyard are expected in farmhouse beers. Distinguish these from faults. Solventy or hot fusel notes indicate high fermentation temperatures or stressed yeast. Diacetyl, with its buttery or butterscotch smell, may result from early packaging or incomplete conditioning. DMS, smelling like cooked corn, often comes from a rushed or inadequate boil.

- Hot/fusel notes: confirm temperature control and consider cooler later stages.

- Diacetyl: allow extra conditioning time for reduction before packaging.

- DMS: review boil vigor and trub separation practices.

When attenuation or flocculation deviates, start with yeast health and pitch rate. Low attenuation can result from underpitched or inactive yeast, poor oxygenation, or lack of nutrients. Building a starter or repitching Saccharomyces improves finish. For low flocculation Brett, accept that Brett often remains active and slow-clarifying. Cold crashing, extended aging, and time in bright tanks will improve clarity. Filtration or fining agents can offer faster results, but use them with care to preserve character.

- Low attenuation: review pitch rate, oxygen, and consider a starter.

- Low flocculation Brett: plan for extended aging and occasional cold conditioning.

- Persistent haze: use fining agents or gentle filtration if clarity is crucial.

Document each change and retest gravity and aroma after interventions. Thoughtful WLP670 troubleshooting maintains farmhouse character while reducing faults and giving brewers control over Brett-driven evolution.

Legal, Safety, and Labeling Notes for Homebrewers

Brewing farmhouse-style beers with mixed cultures requires attention to legal limits, safe handling, and clear labeling. Before scaling a WLP670 batch for friends or sale, read these practical points. Keeping track of alcohol, contamination risks, and consumer information protects you and your audience.

Alcohol tolerance is crucial when setting OG targets. WLP670 has a medium tolerance around 5%–10%. Design recipes that allow fermentation to finish, avoiding stalling. Check local homebrew alcohol limits for gifting or distribution in the United States and plan ABV accordingly.

For commercial sales, licensing and ABV disclosure are mandatory. Many states require producers to follow federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau rules for labeling and production. Even when sharing small amounts, note homebrew alcohol limits to avoid accidental overage.

Sanitation is key to protecting fermentation outcomes and equipment. Brett can persist in porous fittings and hoses. Use caustic cleaners like PBW and follow with sanitizers such as iodophor or Star San. Consider heat or steam for kettles and use dedicated fermenters if you brew many Brett-forward beers.

Handle yeast and starters with care. Store White Labs vials per their instructions, work in clean areas, and disinfect surfaces. Good practices reduce cross-contamination risks and support consistent results when using wild strains.

Labeling builds trust when you share or sell farmhouse beer. Include ABV, a clear style name (for example American Farmhouse Ale or Brett Saison), and common allergens like wheat or oats. Note if the beer carries Brett-driven funk or controlled sourness so tasters know what to expect.

- List batch ABV and bottling date.

- Indicate special ingredients and potential allergens.

- Add a short tasting note describing Brett character and aging potential.

When you combine careful recipe limits with rigorous sanitation Brett control and clear labeling farmhouse beer, you reduce legal risk and improve safety. These steps keep homebrewing rewarding and responsible for both hobbyists and those stepping toward commercial work.

Conclusion

WLP670 offers brewers a convenient way to achieve farmhouse complexity without the hassle of sourcing separate Saison and Brett strains. This blend brings forth bright esters, moderate sourness, and a dry finish with proper management. The consensus from WLP670 reviews is clear: it provides a mixed culture profile with layered flavors, making it accessible for homebrewers and small craft breweries alike.

When fermenting with WLP670, aim for a consistent temperature range of 68°–72°F. Consider a stepped temperature rise to enhance the farmhouse character. Expect attenuation rates of 75%–82% and medium flocculation. Ensure proper oxygenation at pitch and use nutrients like Servomyces when necessary. Extended aging is recommended for pronounced Brett development.

Monitor gravity stability before packaging and be cautious with bottle conditioning to avoid overcarbonation. From a product-review standpoint, WLP670 excels when combined with solid mash profiles and restrained hopping. Adhere to best practices, including correct pitch rates for a 5-gallon batch, careful temperature control, and patience for secondary Brett activity. With White Labs specifications, Briess recipe guidance, and brewer case studies, following these recommendations will yield balanced, nuanced farmhouse ales with reliable results.

FAQ

What is WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend and what does it contain?

WLP670 American Farmhouse Yeast Blend is a White Labs product. It combines a traditional farmhouse/Saison Saccharomyces strain with Brettanomyces. This blend aims to deliver Saison esters and Brett-driven complexity. It's designed for brewers who want a mix of 45% Saison and 55% Brett character.

Which beer styles is WLP670 best suited for?

WLP670 is ideal for Berliner Weisse, Flanders Red Ale, Lambic-style, and wild specialty beers. It's also great for farmhouse ales and Saisons. Brewers seeking Saison-like dryness and spice with Brett complexity will find it suitable.

How does WLP670 compare to using a single Saison strain plus a separate Brett?

The blend offers a simpler approach by combining Saison and Brett characters in one pitch. It can be more cost-effective and easier to handle than using two strains. Expect a balance of Saison phenolics and Brett funk, similar to separate pitching when managed correctly.

What attenuation, OG/FG and ABV ranges should I expect?

White Labs lists attenuation at 75%–82%. Practical examples include an extract recipe OG 1.046 → FG 1.012 (~72% apparent attenuation) and an all-grain case OG 1.061 → FG 1.004 (high attenuation). Final gravities often fall into the low 1.000s; plan OG to hit your target ABV knowing the blend typically finishes dry.

What is the flocculation behavior and clarity outlook?

Flocculation is medium. Initial yeast clearing is common, but the Brett component can maintain haze or slowly alter clarity over time. Extended aging or cold crashing helps settle material, but Brett may keep the beer evolving and slightly hazy long-term.

What is the alcohol tolerance and how should that affect my recipe?

Alcohol tolerance is listed as medium, roughly 5%–10% ABV. For beers above about 10% ABV, the blend may struggle, leaving residual sweetness. For higher-gravity beers, consider a starter, staggered pitching, added nutrients, or blending with a higher-tolerance Saccharomyces strain to ensure completion.

What fermentation temperature range is recommended and why?

White Labs recommends 68°–72°F (20°–22°C). This window balances ester production and lets Brett establish without provoking excessive phenolic or hot solvent notes. The Briess extract example calls for 14 days at 72°F as a practical guideline.

Should I ramp temperatures to accentuate farmhouse character?

Many brewers use stepped ramping: start cool (mid-60s°F) to promote a cleaner early fermentation, allow the wort to self-rise into the high 60s/low 70s, then briefly raise into the low–mid 80s°F for several days to accentuate esters and Brett activity. Return to cooler temps afterward. Ramp slowly over 24–72 hours to avoid stress and off-flavors.

How can homebrewers maintain stable fermentation temperatures?

Use a fermentation chamber or temperature controller with a chest freezer, a swamp cooler, or a heat wrap for small increases. Monitor with an accurate probe thermometer. Avoid sudden large swings and ramp temperatures gradually to protect yeast health.

What pitch rate should I use for a 5-gallon batch?

A single fresh White Labs vial can ferment many 5-gallon batches, but for high-OG or stressed worts make a starter to ensure robust cell counts. White Labs offers a pitch-rate calculator; when in doubt, increase viable cells via a starter.

How should I oxygenate wort before pitching WLP670?

For extract batches, vigorous splashing or shaking during transfer can suffice. For all-grain, use pure oxygen with a stone or vigorous aeration with sanitized tubing and a pump. Adequate oxygen supports healthy Saccharomyces reproduction and helps the Brett establish later.

Should I use nutrients like Servomyces with WLP670?

Yes. Servomyces and other yeast nutrients support vitality, reduce sluggish starts and improve attenuation—especially in recipes with adjuncts (corn, sugars) that lack nutrients. The Briess extract recipe includes Servomyces in the boil for improved fermentation performance.

How long should primary fermentation last and what signs indicate progress?

The Briess extract guideline is 14 days at 72°F. Primary can show vigorous activity in a few days, then slow as Brett continues to metabolize complex sugars. Look for krausen formation, active airlock/bubbling, then settling and steady gravity decline. Gravity stability across several readings indicates a safe point to consider packaging.

Why and when should I allow extended aging for Brett activity?

Brett slowly develops funk, leather, cherry and apple notes over weeks to months. Extended bulk aging (examples include 90+ days) lets Brett refine flavors and slowly attenuate residual sugars. Use extended aging when you want pronounced Brett character and controlled sourness development.

Which fermenter materials are best when working with Brett-containing beers?

Stainless steel is easiest to sanitize and preferred for durability and contamination control. Glass carboys are inert and let you watch fermentation but can break. Food-grade plastic is lightweight and cheap but can scratch and harbor Brett—consider dedicated equipment or strict sanitation to avoid cross-contamination.

Can you provide a sample extract-with-grain recipe for 5 gallons?

A practical 5-gallon Briess-based extract recipe: 3.3 lb CBW Golden Light LME, 0.5 lb CBW Sparkling Amber DME, 2 lb Red Wheat Malt, 2 lb Flaked Yellow Corn, 0.5 oz Crystal hops (60 min), 0.75 oz Crystal (15 min), 1 vial WLP670, 1 capsule Servomyces (boil 10 min). Mini-mash at 152–158°F for 30 minutes, add extracts, boil, cool to ~72°F, oxygenate, pitch. Expected OG ~1.046, FG ~1.012, ABV ~4.7%, IBU ~15.

What mash temperatures should I use for all-grain farmhouse ales?

Mash between 152–158°F. Lower (~152°F) yields a very fermentable, drier saison-like beer. Higher (~158°F) provides more body and residual sweetness. Brewers aiming for very dry beers sometimes mash even lower (e.g., 149°F) for extended time to increase fermentability.

What adjuncts and specialty grains enhance farmhouse character?

Use wheat malt, flaked oats, golden naked oats, flaked corn, Belgian Caravienne, rye or small amounts of crystal malts. Wheat and flakes add mouthfeel and rustic character; simple sugars or corn increase fermentability and dryness. Keep specialty malts low to preserve yeast-derived flavors.

What IBU range and hop choices work well with WLP670 beers?

Farmhouse beers commonly fall between 10–25 IBUs; Briess example uses ~15 IBU. American citrus/floral hops (e.g., Amarillo) complement Brett and esters; noble or spicy hops suit traditional Saisons. Favor modest bittering and measured late additions or dry hopping so yeast character remains central.

How does the Brett in WLP670 influence flavor over time?

Brett produces complex notes—leather, cherry, green apple, barnyard funk—that emerge and evolve over weeks to months. Initially subtle, these flavors intensify with extended aging as Brett slowly metabolizes remaining substrates and develops oxidative and fruity complexities.

How can I control moderate sourness when using WLP670?

Time is the main control—shorter aging limits acid development. Monitor pH during conditioning. If beer becomes too tart, blend with fresher, non-sour beer to balance acidity. WLP670 does not include acid-producing bacteria by design, so sourness tends to be moderate and gradual.

What sanitation steps prevent Brett cross-contamination?

Use rigorous cleaning and sanitation with caustic cleaners, PBW, and sanitizers like iodophor or Star San. Consider dedicated fermenters, hoses and racking equipment for Brett beers. Steam or hot-water sanitize fittings where possible, and segregate Brett work to limit contamination of neutral styles.

What labeling should I use if sharing or selling farmhouse beers?

Label beers with ABV, style descriptor (e.g., American Farmhouse Ale, Brett Saison), and allergen info (wheat, oats). Include tasting notes indicating Brett funk or moderate sourness and suggested cellaring advice so consumers know what to expect.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like these suggestions:

- Fermenting Beer with CellarScience Monk Yeast

- Fermenting Beer with White Labs WLP028 Edinburgh/Scottish Ale Yeast

- Fermenting Beer with Mangrove Jack's M21 Belgian Wit Yeast